When artists paint they put part of their emotions, feelings and interpretations

into something they like or admire, placing it before the public as a transitional

object from which people pick up on different brushstrokes depending on how they

are feeling; thus Picasso moved from Cubism to animate beings, in a way that expressed

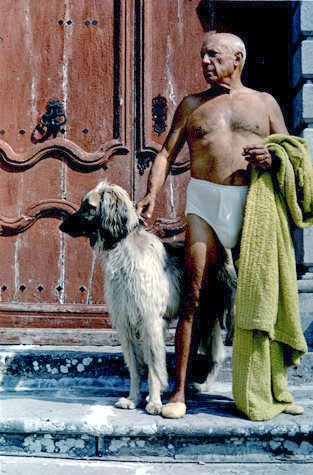

what he himself was feeling. There was nothing terribly extraordinary about Malaga-born

genius’s relationship with dogs, as can be glimpsed in the many photographs in which

he is pictured with one of these animals. The genius needed time to create and,

just like his father, who felt an attraction for the pigeons he painted and sometimes

fed in the Plaza de la Merced in Malaga, or admired in his friends’ dovecotes, Picasso

felt an attraction to dogs, but he did not have the time to spend on them so both

he and his father before him began to paint the animals which meant so much to them.

Once he had left his Cubist phase and his "near" social autism behind, Picasso saw

dogs as loyal animals which did not judge him or give him funny looks but, as he

was highly critical of his own emotions he did not feel either physically or emotionally

equipped to look after one of these magnificent creatures, although he did feel

comfortable with them and was intrigued by the beautiful bond between men and dogs.

As a result of this, although dogs are a constant in the maestro from Malaga’s painting,

and he enjoyed not only painting them but being photographed with them doing all

sorts of everyday things, as we have noted above, he never wanted to own a dog himself,

instead passing the responsibility on to his partner or children, or else he would

simply look after a friend’s pet for a while or paint and draw animals he knew and

liked.

Psychology tells us that if we ask children to draw an animal, their choices can

tell us something about their characters and certain hidden desires. Children who

choose to draw a dog show a kind-hearted, loyal character, effectively depending

on the people close to them, and their generosity is firmly based on the need to

have lots of friends around them with whom they can play, amuse themselves and have

fun. This is the prototype of the "pampered" child and if they are unable to gain

their companions’ approval, they become sad and melancholic. Although usually generous,

sometimes when asked to do something they may start grumbling and snorting, in other

words protesting, but this soon passes. Another ability that children of this kind

have is that they can seem to have a sixth sense about people... THEY CAN GROW UP

TO BE GREAT SEEKERS, RESEARCHERS, POLICE OFFICERS, PSYCHOLOGISTS OR CREATIVE ARTISTS

- Picasso was a seeker, a researcher and a great creative artist.

This hypothesis about Picasso’s character is something I share with the dog breeder

and psychologist Dr V.G. Mancuso. In his case it is due to his profession and in

my own also because of the fact that I have studied morphopsychology and graphology.

From one of the great biographers of the painter and his work, Rafael Inglada, and

also from notes taken from my own personal archive, what follows is a list of animals

which accompanied Picasso, either in his life or work, or in both facets:

Clipper (La Coruña, 1891-1895), a "mutt" he painted in 1895. He was not the

dog’s owner.

Feo (Paris, circa 1904), another "mutt" he painted in 1904-1905. He was not

the dog’s owner.

FRIKA, a mixed-breed bitch which Picasso and Fernande Olivier took along

for company firstly in the Bateau-Lavoir (circa 1904-1909). Soon afterwards they

took in another dog, *Gat. In 1907, and Picasso did drawings of the dog with

her

pups. In 1909, when he moved to 11 Boulevard de Clichy, Frika once again

lived with

Picasso, alongside *Monina and a few *cats. A year later (1910), she travelled with

Picasso and Olivier to Cadaqués. In 1912, after Picasso’s relationship with Fernande

Olivier ended, the bitch was left in the hands of Georges Braque for a number of

days, and when the latter was sent to Céret, Picasso and Eva Gouel looked after

her.

GAT. The dog which accompanied Picasso – together with *Frika – in

the Bateau-Lavoir

for a while (1904-1905). In December 1904, Picasso produced a pencil drawing on

paper called “The actor”, a character study with heads of Fernande in profile, hands,

ear and the dog Gat (private collection). She may have died in 1906.

A wire fox terrier whose name we do not know. A dog which may have been given

to Picasso and Fernande Olivier by Miquel Utrillo in Barcelona, when the pair of

them travelled to Gósol (Lleida) in May 1906. From there they wrote to Guillaume

Apollinaire on 21st June of that year, telling him that they had been

given the

dog in Barcelona.

Sentinelle (Avignon, 1914), another dog he looked after, although it actually

belonged to the painter André Derain, who also drew it.

Bob (Boisgeloup, 1930s), a Saint Bernard. We do not know for certain whether

it belonged to him or was lent to him temporarily by friends.

Noisette (Paris, 1930s), an Airedale which was taken on a trip to Barcelona

in 1933 (he appears to have owned this dog). This was a breed that was very popular

with the intellectuals of the time, as was the case with Francisco Pino, a famous

poet from Valladolid.

Ricky (Paris, 1940s), a poodle, which seems to have belonged to his daughter

Maya.

Kasbek (Paris, 1940s), an Afghan which he drew on various occasions in the

1940s.

Yan (Cannes, 1950s), a boxer which he also painted.

Lump (Cannes, 1950s), a dachshund which belonged to Duncan and which he painted

on a plate. The dog died in 1973, the same year as Picasso himself.

Perro (Cannes-Vauvenargues, 1950s-60), a Dalmatian, painted by Picasso on

numerous occasions, the dog did not belong to him.

Kaboul (Vauvenargues-Mougins, 1960s), an Afghan.

Sauterelle (Mougins, 1960s-1970s), an Afghan.

Igor (Mougins, 1970s), an Afghan which belonged to Jacqueline and died after

Picasso.

Conclusion: The great legend of twentieth century Cubist painting liked dogs, but

never really had one of his own. Instead he delegated responsibility for the animal

and looking after it to his family, friends or partners because, in a self-critical

sense, he had the self-awareness to realise that he would not be a good owner for

an animal. To paraphrase Saint-Exupéry, Picasso never had the privilege of allowing

himself to be domesticated by this wonderful animal.

Dr Vincenzo Gianluca Mancuso (psychological part) and Rafael Fernández de Zafra

(historical part)